What are (plains and woodland) indian reproductions?

Period Indian items are called originals or artefacts, whereas products that respect the characteristics, i.e. style, proportions, materials and design of period Indian objects, especially those from the 18th and 19th centuries, are called reproductions. A reproduction does not necessarily have to be an exact and detailed copy of a particular artefact, but it can be.

Most reproductions on the market today focus on the cultures of the Great Plains or Eastern Woodland Indians.

What are not indian reproductions

Most Native American style products offered on the contemporary market, especially in various “ethnic” or “western” stores, cannot be considered Indian reproductions. Such products include dream catchers, talking sticks, war bonnets made of chicken feathers or similar novelties. Most of these products are cheap trinkets, often mass produced in China or India for tourists and have very little in common with real Indians and their material or spiritual culture.

Contemporary reproductions and their shortcomings

Only a tiny fraction of the Indian reproductions produced today are historically accurate and authentic, with the majority possessing neither of these characteristics. Based on practical experience, I have attempted to summarize the major errors made by makers of Indian reproductions.

Sin no. 1 - Ignorance of time periods and tribal frameworks

Original Indian artefacts were created in relatively narrow time periods and tribal frameworks. Over time, each tribe developed its own specific style, which also changed with the times. This was a process of natural evolution, but also subject to the availability of materials. For example, seed beads were not available on the plains before 1840, bone hair pipes were not available again until after 1870, certain colours were only used in certain periods, and so on. For those artefacts that survived, it is therefore relatively easy to determine, based on their characteristic elements, when they were made and what their tribal origin is.

Ignorance of the period and of tribal identities and patterns is by far the biggest and most widespread problem among makers of Indian reproductions. Many have absolutely no idea that these frameworks exist and that they are quite strictly defined.

Those who lack such knowledge create nonsensical products in terms of shape and design, with little or no respect for time periods and tribal frameworks. Many arbitrarily mix patterns from different tribes or different periods, creating a chaotic mishmash. The insensitive application of creative license subsequently completes their destructive work.

The resulting products are often completely meaningless from an ethnographic and historical point of view.

Good makers know the time periods and tribal frameworks very well, which is reflected in the accurate representation of tribal designs from a specific period of time. To do this and work effectively, they often reference their own extensive databases of photographs of originals from museums and private collections, as well as collections of period paintings.

Knowledge of time periods and tribal frameworks can be acquired from/by:

- consulting specialised books and catalogues of private and museum collections, auction houses or galleries;

- studying originals directly in museums or in private collections;

- looking up photographs on the Internet, either on the websites of museums, private collectors or galleries and auction houses that deal with originals;

- studying period photographs and pictorial records.

Although studying originals from pictures is valuable, there is greater benefit in seeing the originals in “real life” and in being able to “touch” them. One then has the opportunity to study the details, to feel the weight of an artefact, and to assess the materials (softness, flexibility, thickness of the hide, etc.), which is not possible to determine from photographs.

Sin no. 2 - Too much imagination

Applying creative license is not bad in principle, but it must be done sensibly. Time periods and tribal frameworks offer artists some scope to do this. There is no need to slavishly copy a pattern or design and create an exact replica. It is possible to create one’s own designs. However, this must be done with great care and sensitivity to a given time period and tribal style.

As is often the case, less is more. In other words, keep the creative license in check and stay true to the original. This is especially important with regards to embroideries, painting designs and various decorative elements. Too much creative license can generate a pattern that moves beyond the time period and tribal framework. The excessive application of decorative elements (especially to increase the visual appeal of a reproduction) often leads to a reduction in a reproduction´s “credibility”.

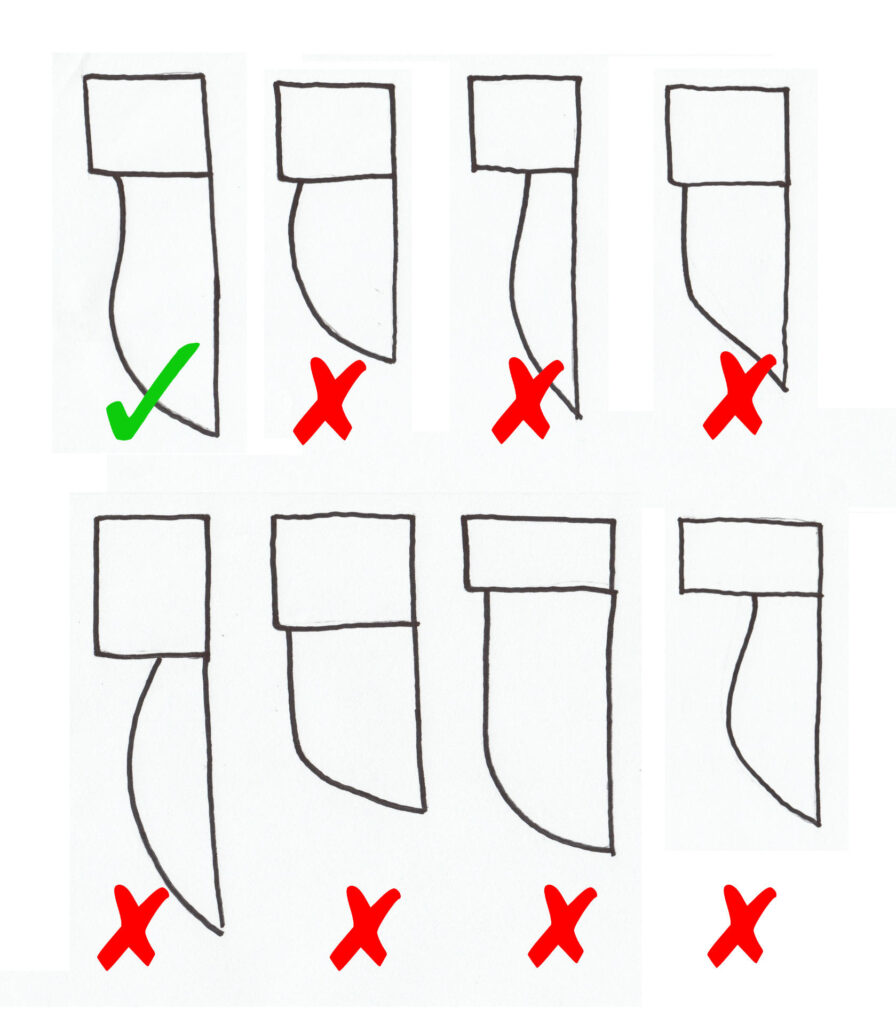

Sin no. 3 - Incorrect proportions and dimensions

Indian artefacts have very specific proportions, often being narrow, slender and graceful rather than stout and short. This is due to the refined Indian sense of aesthetics.

Ignoring proportions is a common mistake even among more skilled makers of reproductions. The products are often too large or too small, or the proportions are all wrong. The products look unbalanced, malformed, elongated, or simply strange.

A poor reproduction can be recognised at a glance by its hammy form, non-Indian silhouette or incorrect proportions.

For example, many Indian pipe bags taper visibly upwards, but most makers make these bags rectangular because they don’t think to apply this design element at all.

Product proportions need to be sensitively perceived and maintained, as do original dimensions and sizes. All these parameters play an important role.

Sin no. 4 - Use of inauthentic materials

Poor awareness of historical authenticity goes hand in hand with the use of inauthentic materials. The use of inauthentic and non-original materials diminishes the level, value and credibility of a reproduction.

Some makers of Indian reproductions utilise inauthentic materials to save money, because they do not have access to authentic materials, or because they are not familiar with them.

In contrast, good makers of reproductions utilise the same materials as 18th and 19th century Indians and avoid all substitutes and simplifications whenever possible.

LEATHER

The use of commercially tanned leathers is always a major compromise. Such leather can be recognised at a glance and greatly reduces reproduction´s authenticity. Indians in pre-reservation times used only brain tanned hides. However, brain tanned hides not only differ in terms of quality (thick, thin, soft, stiff) and origin (deer, elk, antelope, bighorn sheep), but also in the method of processing (wet or dry scraping), which affects texture. All this can be seen in the final product.

It is also a mistake to use hides that are too thick and stiff or, conversely, too soft and thin where this is not appropriate. For example, period Indian clothing was almost always made from very thin, soft skins, so it is a mistake to use thick or stiff skins for this purpose. Similarly, it is a mistake, for example, to use too thin leather for fringes because Indians generally used thick leather for these.

FABRICS

Most amateurs buy the first cloth they come across in a shop, usually red or blue. However, 19th century wool fabrics had their own texture and came in a fairly narrow range of shades, as determined by the dyeing techniques of the time. Many originals also feature a white undyed edge, which was created during the production of the cloth and was considered a decorative element by the Indians.

Today, fairly good quality and historically correct saved list cloth reproductions can be found on the market, but they are not cheap. Some people try to make and dye their own saved list cloth, but this usually doesn’t turn out well.

BEADS

The quality and authenticity of the beads largely determines the authenticity of the reproduction. Period beads in the 19th century had specific shades and sometimes irregular shapes, which distinguishes them from contemporary beads, which are too round, too uniform and too bright in colour. “Old beads”, whether original 19th century beads or high quality reproductions, are not cheap and are hard to find, yet they are worth investing in. The use of “modern beads” with their bright, “chemical” colours is the domain of beginners and amateurs.

PORCUPINE QUILLS

Only very few quillworkers can dye quills to look like those from the 19th century. One must have a good eye and talent for observation, as well as study originals and experiment a lot with colours to achieve period hues. It is a very difficult, long-term work.

Quills that are too luminous in colour or differ in shade to period originals are typical of beginning quillworkers or advanced quillworkers that lack sense of colour.

THREAD

The use of linen or cotton thread or artificial sinew for sewing, where the Indians used real sinew, is also a mistake. This is especially true with regards to completing products and for embroidery. Embroidery done with genuine sinew looks different from embroidery done with cotton thread, in particular when it comes to bead embroidery. For some purposes, the Indians used linen or cotton thread, but only where it was desirable, such as for the tacking thread in overlay stitch and the like.

Sin no. 5 - Unskilled technique

This comes down to the failure to master certain techniques, whether it be beadwork, quillwork, painting on leather, making rawhide or any other technique. The poor application of such techniques is clearly visible on products at a glance.

Typical examples include waves in a lane stitch or even in an overlay stitch, beads sewn too close together, unsightly renditions of porcupine quillwork, jumping rows and visible gaps between quills, none of which would be visible on the old originals.

Sin no. 6 - Technical design and cold appearance

The opposite extreme is an overly technical design. Many makers use rulers and callipers when measuring a reproduction, embroidery or painting, drawing all the proportions and lines as if it was a technical drawing. The embroidery is then stitched in such a way that one stitch is exactly the same as the next, as if the embroidery had been done by a sewing machine.

Technical embroidery or painting, or an overly technical design that results in an cold, industrial, sterile, “chemical” appearance is a serious flaw that greatly reduces a reproduction´s authenticity. Such characteristics radiate from reproductions and are easily noticed by people more sensitive to these issues. A sterile product has no soul and is actually dead.

Making an Indian reproduction is not just a technical matter, the artistic aspect cannot be underestimated or completely ignored. Period Indian artefacts are never sterile. They always have a distinctly human dimension, hence certain design and technical flaws.

Sin no. 7 - Faulty patina

Most makers of Indian reproductions apply a patina to them to make them look old or at least used. This is to avoid the reproductions looking too sterile. The appropriate application of a patina is not easy. Finding good and appropriate patination procedures is a process that takes many years.

The following errors can be made with patina: too much patina, no patina at all, and inappropriate patina.

Some makers apply “buckets” of dirt to their creations, often to cover up the sterility and inauthenticity of the materials used. The reproductions then look as if they have been lying in mud for 150 years. Some people may be comfortable with this because they succumb to the illusion that they are holding a 200-year-old artefact. In reality, even old originals can be remarkably well-preserved and in good condition if properly stored.

The other extreme and error is the complete lack of patina, where reproductions glow with newness and positively shine. When combined with sterile workmanship, this is a deadly cocktail.

The use of inappropriate methods, such as the application of “dirt” to places where it could not normally be, etc., is also a mistake. This creates an effect that never occurs on the originals.

The patina often looks implausible because some parts of the reproduction are extremely patinated, while other parts shine with newness. The patina of the different parts must be in harmony with one another, otherwise the credibility of the reproduction is greatly diminished.

The patination gives a reproduction some evidence of use and age. However, patina should always be applied judiciously, with sensitivity and as little as possible. A good artist will always apply patina only imperceptibly to make the piece look natural.

(Sin no. 8 - Aesthetic dysfunction)

The eighth sin, which is an addition to our list, is, from a certain point of view, not a sin at all. It is in fact about the aesthetic and artistic ability of each artist, their ability to perceive beauty and harmony. This is, more or less, inborn and cannot be taught. There is no way to compensate for a lack of talent.

Even though not being artistically gifted cannot directly be considered a sin, I believe it is worth mentioning.

The design itself is very important. Even if a reproduction is made from authentic materials and is accurate in terms of time period and tribal framework, its design may be weak or unbalanced. Alternatively, it may be too expressive and cluttered. Even among American Indian originals, there are things that are excellent, mediocre and below par in design. The ideal reproduction is not only completely authentic, but also balanced in design. This always depends on the artist´s sense of aesthetics.

A weak, bland or too expressive design is not technically a fault. After all, even period originals can be like that. However, a balanced and refined design shows the aesthetic maturity of the creator, which can only work to their advantage.

Summary

The overall appearance, authenticity and quality of an Indian reproduction depends on a combination of factors, namely architectural authenticity, adherence to time periods and tribal frameworks, compliance with the dimensions and proportions of various design elements, the use of authentic materials, the technical proficiency of the artist, their ability to apply patina sensibly, their aesthetic maturity, and others.

It goes without saying that this list of sins is by no means complete; only the most serious ones are listed. If you can avoid them, or at least learn from them, good for you.