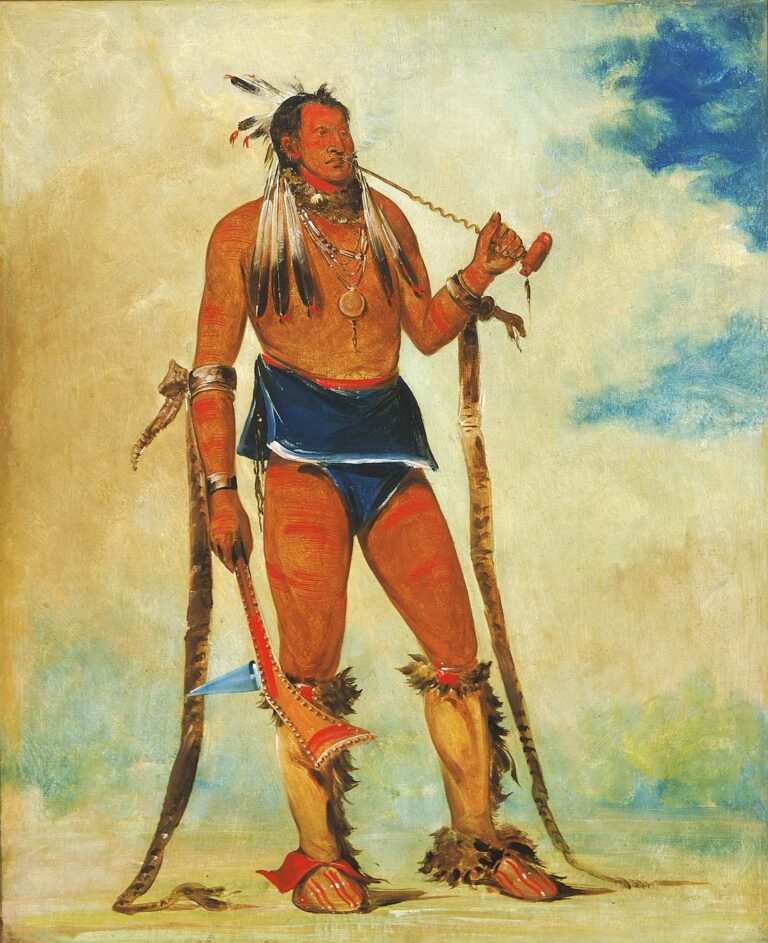

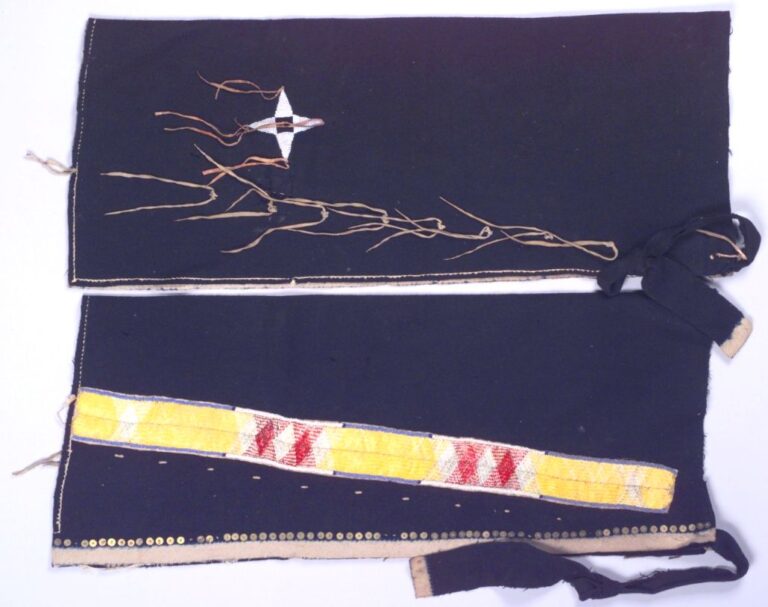

The Plains Indians were very fond of the woollen cloth supplied by the white traders, skilfully making clothing and every other conceivable article from it. The white, undyed lists with jagged edges were a typical feature of these fabrics. Woollen cloth, most often scarlet or dark blue in colour with a typical white undyed jagged edge about 3 cm wide, appears on a variety of Indian artefacts, from leggings, war shirts and dresses to headdress hangings. The answers to the questions about the origins of the undyed edge and its significance will be revealed a little later on.

Manufacture of woollen cloth

Until at least the end of the 19th century, the vast majority of woollen fabrics were imported to the USA from England. From the 12th to the late 19th century, England was the clear hegemon in the processing and export of wool and woollen fabrics. The quality of English wool products was unsurpassed and no other country could compete in this field.

Whether their country is hot or cold, steamy or freezing, it's always the same, both at the equinox and near the solstice, the English wool producers dress them all.

Daniel Defoe, 1724

The wool industry was the most important industry in England until the end of the 19th century. It employed more people and made more money than all other industries combined. Only domestic wool, which was said to be of the highest quality in the world, was used for the production of woollen fabrics. From the 18th century, machines did most of the work.

The dyeing process

The dyeing of the fabric could be done either by dyeing the yarn or by dyeing the whole fabric when it was finished. The second option was cheaper and more practical and produced better results. Specialist dye houses were used to dye “in the piece” (finished fabric). Most were located in London.

The dyeworks consisted of huge vats of dye and a system of winches, pulleys and rollers. Fabric up to several dozen metres long was stitched together at the ends. It was then mounted onto rollers on which it moved, repeatedly being dipped into a vat of dye and pulled out again. Alternatively, the fabric was simply hung on a rope and plunged into the vat of dye using a tiller. In other cases, the cloth was pushed between two rollers to enable the dye to better penetrate the cloth.

The most common colours during the 18th and 19th centuries were dark blue and scarlet, and occasionally green and yellow.

Blue

The blue colour was originally obtained from indigo and dyer’s woad (Isatis tinctoria). Indigo is a legume native to East India. It has been used for dyeing for at least 5,000 years. In Europe, it has been used to dye blue fabrics since the Middle Ages. Indigo is a very high quality and stable dye that does not fade over time. This is due to the fact that it binds to the fabric chemically. It produces a rich dark blue colour. Most of the woollen fabrics imported into the US during the 18th and 19th centuries were dark blue and most of them were dyed using indigo. Dyer’s woad (Isatis tinctoria) is a herb native to Europe. In terms of dyeing ability, it is a weaker version of indigo. It was used in Europe as the main source of blue dye before indigo was imported from India. After that, its use began to decline.

Red

The red dye was extracted from carmine or cochineal (produced from the dried females of a certain beetle from Central South America) and from the root of the Rose madder (Rubia tinctorum). Rose madder was used as the main European red dye before cochineal was discovered (this happened in 1518 in Mexico). Cochineal produces a distinctive light red colour that does not fade in the light. Substances dyed in rose madder, on the other hand, tend to be darker. The most desirable bold red cloth was called “Stroudwater cloth” because it came from the Stroud area. A combination of cochineal and stannous chloride was used to dye it. It was from this cloth that the famous red British uniforms were made.

Yellow

The yellow dye was extracted from Indian mulberry (Morinda citrifolia). The colour is not very stable and fades. The colour varies from mustard to light lemon. Most yellow substances are now faded. It was used very rarely on the plains, mainly for edging blankets and bedspreads or bonnet hangers.

Green

A mixture of Indian mulberry (Morinda citrifolia) mixed with indigo was used to dye the green fabric. In the 18th century it was made from yellow campeachy wood mixed with copper. In the 1740s, an extract of indigo mixed with natural yellow began to be used. The result was so-called Saxon green. Although this green colour was quite pronounced, it easily fades. As a result, most of today’s surviving specimens are a pale olive colour. Due to the rapid fading, there was little interest in this fabric.

Synthetis dyes

The first aniline-based synthetic dyes began to be used in the wool industry in the 1850s and 1860s. It is documented that synthetic dyes were already being used by the Plains Indians during the same period. By the 1880s, aniline dyes were available for home use. The main reasons for using synthetic dyes were economic. They were much cheaper than natural dyes, were stable in colour, and provided a wider range of shades.

The saved list

The white, undyed list of the fabric, with its typical jagged edge, is created on the same basis as batik. A strip of thick linen is folded in half and attached to the edge of the fabric, which is then rolled, or folded and wrapped, and stitched with a thick thread with stitches about 5mm apart. The thread was tightened as much as possible and the woollen fabric inside the linen then firmly pressed. During the dyeing process, the edges of the fabric remained undyed, white, the natural colour of the cloth. The typical “teeth” are the impressions of the thread. The thread holes are also usually clearly visible. The typical width of the indyed edge is 2.5 to 3.2 cm, but on some specimens it can be up to 5 cm wide.

The reasons for protecting the edges of the fabric from the dye were purely economic. Both lists of the cloth contained so-called selvedges, about 2-3 cm wide. The selvedges were reinforced compared to the rest of the fabric. The purpose of the selvedges was to prevent the fabric from fraying at the edges. These selvedges were cut off by tailors before sewing because they disturbed the uniformity of the fabric. In some cases, they were sewn into the seams so that they would not be visible.

The selvedges were therefore part of the fabric that mostly ended up as waste. Since natural dyes were extremely expensive, efforts were made to be as economical as possible. Protecting the selvedges from being dyed was a way to save precious dye. This was the real reason for the white, undyed edges.

As the edges of the cloth were hand-sewn into the linen, it is logical to presume that, in all likelihood, the cost of this work exceeded the losses caused by the dyeing of the hems. However, this is only today’s point of view, when human labour in Europe is extremely expensive compared to the cost of materials. In the 18th and 19th centuries, however, it was the other way round: the value of human labour was much lower compared to the cost of materials or raw materials.

While local tailors cut the white edges off as waste, the Indians were fascinated by them. They loved the white stripes and tried to arrange them so that they were as visible as possible. For them, the white stripe was simply an important design element. Some even attributed supernatural, magical properties to it.

The Indians directly demanded white edges on the cloth from the traders. This demand resulted in the fabric still being produced in this way in England even at a time when cheap synthetic aniline dyes had entered the market and protecting the edges from dyeing had become meaningless. White undyed edges on fabric appeared in Canada well into the mid-20th century.

The earliest record that mentions an undyed list dates back to 1704. Thomas Banister of Boston, enquired in a letter to London about a suitable cloth with a white edge for trade with the Indians.

James Logan, a Quaker teacher and New England merchant, wrote in his diary in 1714:

The Stroudwater red and blue are mainly sold, not only the fabric and its colour valued, but also the list, which the Indians are particularly curious about. This is a white strip about two fingers wide.

James Logan

Notes

- The quality, especially the strength of period fabrics could vary from coarsely woven to very finely woven.

- The contours of the undyed list could also vary greatly, especially in the size and regularity of the teeth, the width of the stripe, the degree of colour bleed-through, and so on.

- Both twill and plain weave products can be seen on period originals.

- The black stripes in the white lists of some fabrics are made by weaving in black yarn.

- Most of the red cloth is very bright, probably Stroudwater cloth dyed with cochineal and stannous chloride. Dark red fabrics may be the result of synthetic dyes or dyeing with rose madder.

- The common width of woollen cloth in the 18th and 19th centuries was 120-140 cm. Today’s cloth width tends to be around 150 cm.