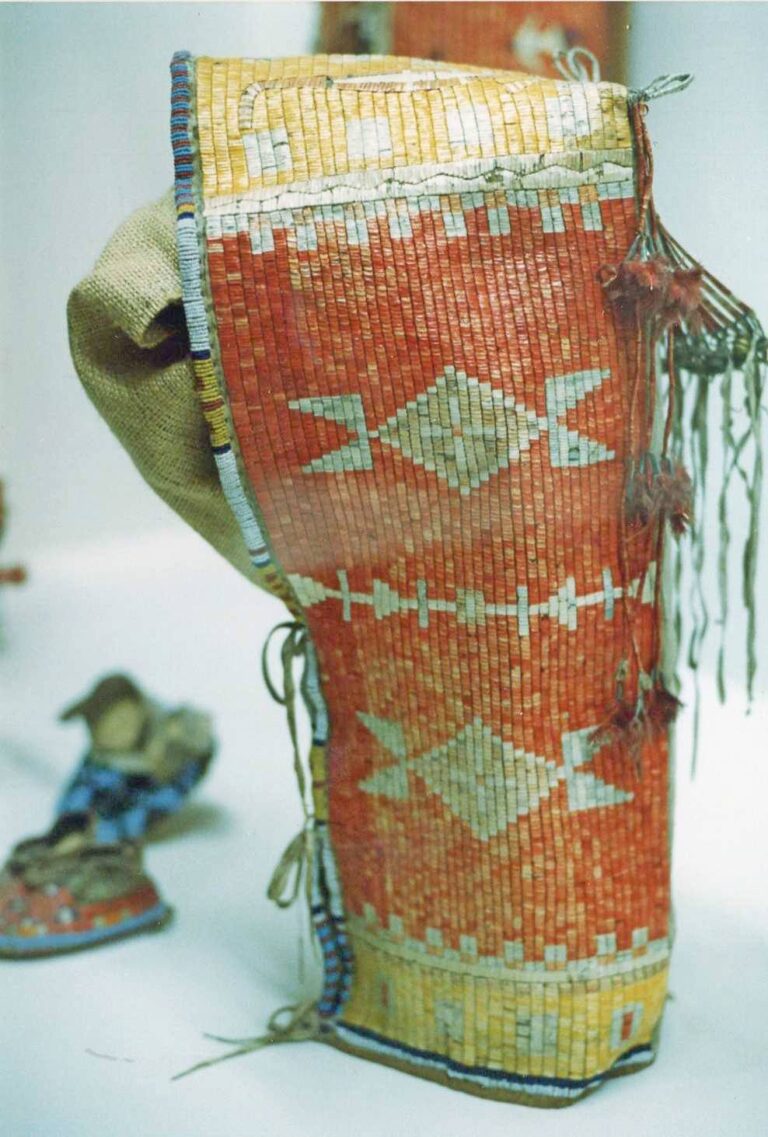

Porcupine quillwork decoration was widespread in most northern regions of the North American continent in pre-reservation times. Prior to the contact with whites, who introduced glass beads to American Indians, porcupine quillwork decoration was the predominant decorative art technique. After the Indians acquired glass beads, the amount of quillwork decoration decreased, but the quills were still in use, and the art has persisted among the American Indians to the present day.

The main decorative techniques included wrapping (strips of rawhide, birch bark or deerskin), sewing quills onto leather or birch bark, plaiting multiple quills or weaving them into a warp.

History

Decorating with porcupine quills is an ancient, exclusively American Indian technique. The earliest surviving tools used to make quillwork date back to the 6th century AD. However, quillworking is probably even older.

Quillwork likely originated in areas where the Canadian porcupine, the animal whose quills are used for quillwork, lives: the coniferous and mixed forests of North America. However, it gradually spread to other parts of the North American continent as the quills were traded.

Interestingly, some tribes, especially in the Great Plains (such as the Lakota, Nakota, and Dakota, but others as well) produced vast quantities of quillwork even though no porcupines lived in their territory.

Quillwork techniques likely came to the Great Plains from the Northwestern forests, where there was a very long tradition and a relatively narrowly defined style of quillwork. During the colonization of the North American continent by Europeans, there was pressure on the eastern tribes, who then pushed further west. Some tribes, especially those from the Great Lakes region, were pushed out to the Great Plains, where they brought with them the culture of quillwork.

Initially, the design and techniques of quillwork in the Great Plains were based on those from the Eastern Woodlands, but over time the Plains tribes developed their own specific designs and decoration techniques.

The mythical origin of quillwork

The Indians themselves explain the origin of quillwork through colourful legends, as is common among them. The Indians believe that all things are communicated to them through dreams and visions. Each tribe has always had its own such legends.

For example, the Lakota believe that the art of quillwork was taught to them by the “Double Woman”, a mythical being who appeared to a woman in a dream and showed her how to work with quills and how to create decorative patterns. The instructed woman then passed on the knowledge to her fellow tribeswomen.

In general, the Lakota believe that those women who dream of the Double Woman will be highly skilled and blessed in artistic expression, and that the objects made by them will be a blessing to those who possess them.

Quillwork evolution

Altogether, there are several dozen different decorative quillwork techniques. Each one is always related to specific patterns and is then associated with a particular tribe or cultural area. Thus, according to the technique and the pattern used, the approximate time and area of origin can be determined.

Different techniques are differently demanding. It can be assumed that quillwork techniques evolved from the simpler to the more complex and demanding.

Wrapping

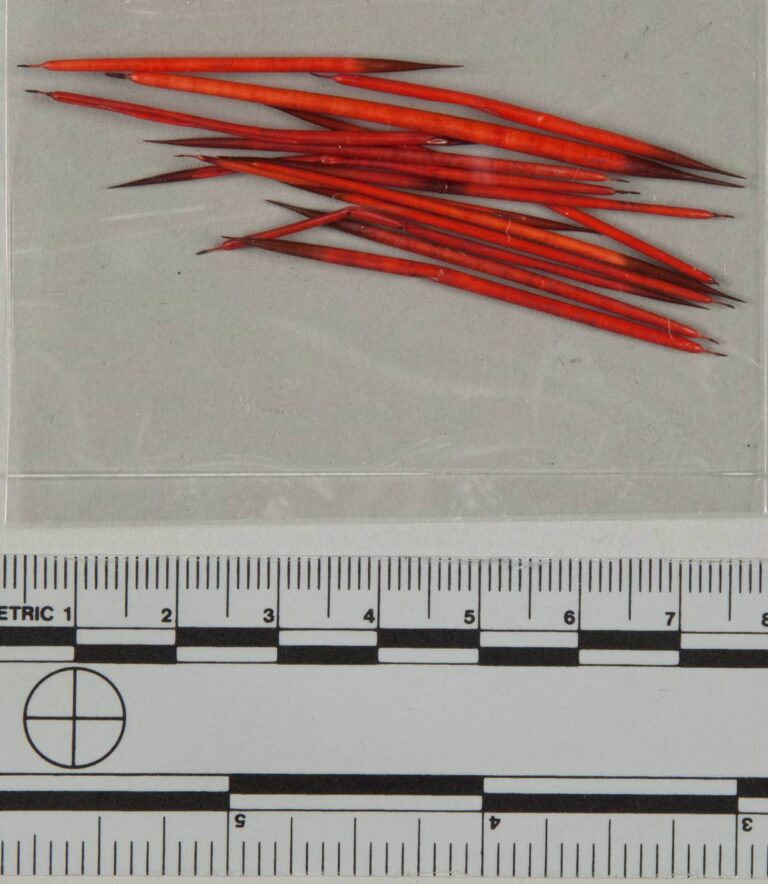

The earliest technique seems to be the wrapping of strips of birch bark, later rawhide or other materials. Such a technique is the simplest, as the quills need only to be artfully wrapped around the material and no other special tools are needed. As the quills are relatively short (about 5 cm), they need to be frequently spliced.

Quillwork embroidery

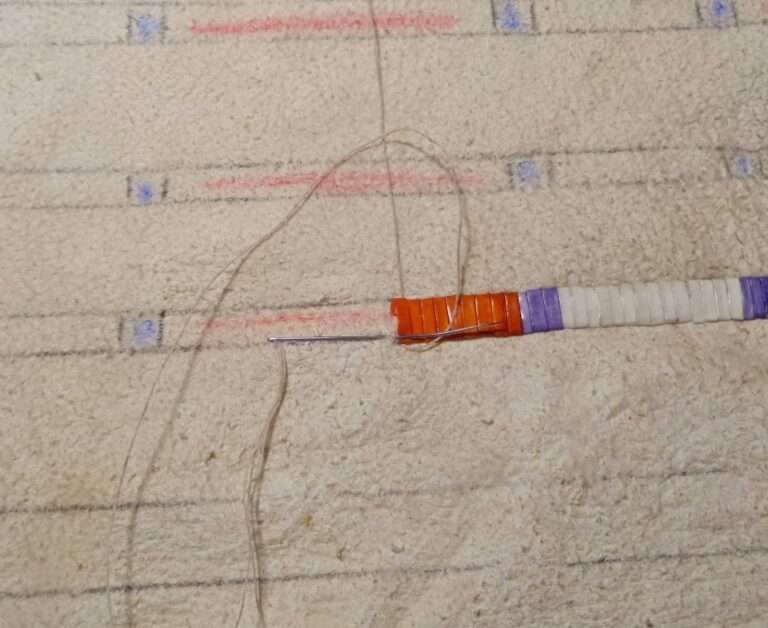

A more difficult technique consists in sewing the quills onto a piece of tanned leather. For this, thin threads made from a backstrap sinew of a deer, elk or other animal were used. Holes were punched through the skin surface, using a thin, sharp awl made of a antlers, bones or bighorn sheep horns (later iron awls were introduced).

Thin sinew threads were then passed through the pre-pierced holes, the ends of which had previously been stiffened by dipping them in glue so that they would not fray. These threads then held the flattened quills in place.

It was only later, in the post-contact period, that the Indians acquired steel needles from white traders, which made their work much easier. It was no longer necessary to pierce the leather with an awl, as the craftworker could sew directly with a needle.

Embroidery is generally more difficult than wrapping. In addition to the quills, a leather base is required, and sinew threads, which are quite difficult to make, as well as needles or sharp awls.

There are a number of stitches and quillwork techniques where the quills are sewn onto leather. The simplest and probably the oldest is the zig-zag technique, which originated in the Eastern Woodlands, but was also commonly used in the Great Plains. Slightly more difficult is the so-called simple band technique. In both cases it is embroidered with a single quill. When the entire quill is worked into the stitch, it is spliced with another quill and so on.

However, there are techniques where multiple quills are embroidered simultaneously. Such stitching techniques are very demanding of skill and imagination. They are called “plaited quillwork” or “multiple quill plaiting”. The quills are intertwined one over the other and sewn onto the leather at the same time. There are many techniques of intertwining, and it is beyond the scope of this article to describe them all. The intertwining techniques are certainly younger than the techniques using only one quill at a time.

One of the most difficult but most fascinating techniques is “quill-wrapped horsehair”. The quills are wrapped around a bundle of horsehair and at the same time sewn to a base of tanned leather. This creates a unique three-dimensional effect. This technique was used mainly by the Plateau tribes, but also by the Crows. I have written a separate article about this technique.

Processing and storage of quills

Quillwork, like all other decorative techniques, was exclusively women’s work. The quills were first plucked out from a porcupine hide, then sorted by size and length, as different techniques require different thicknesses and lengths of quills.

Then the quills were dyed. For this, natural dyes were used, mainly of plant origin, such as roots, berries, peels, etc. After 1850, commercial dyes from whites and even later aniline dyes began to be used on the plains.

Among the earliest colours in the Great Plains were light yellow, light blue, orange, red, and brown-black. Green or purple were rarely used on the plains. The quills were dyed in pots of warm, but not boiling water and a dye essence.

The women kept the dyed and sorted quills in special bags made of buffalo bladders. Some bladders may have been beautifully decorated.

Working with quills

Working with quills is quite demanding and each technique requires a great deal of skill, patience and training. For most techniques, the quills need to be softened and flattened before processing, as they are originally hard and round in cross-section.

The Indian women achieved this by moistening the quills for a period of time (at least about five minutes). The moistened quill will soften considerably and can be flattened at this stage.

Indian women used their own mouths to moisten the quills. Enzymes in the saliva would soften the quills perfectly within few minutes. When an Indian woman flattened and processed a quill, such as sewing it onto a hide, she could simultaneously moisten one or two or three other quills in her mouth. In this way she maintained a regular rhythm of work.

An alternative method of moistening was to cover the quills with moist clay. Among some tribes, this was considered the traditional method.

The flattening could be done with a special tool, a flattener. Usually it was a piece of smoothed deer antler, bone, or wood, which was run over the quill on some hard surface (such as a wooden board).

An alternative option for flattening was to pull the quill between the teeth or to flatten it with help of the nails.

For better flattening, sometimes the Indian women would cut off the tip of a quill, or part of the root, so that all the air from inside could escape and the flattening would be really thorough.

Once flattened, the quill is still moist and supple and can be worked, wrapped or sewn. This should be done relatively quickly, as in a few minutes the quill will dry out again and thus stiffen, but will remain flattened.

The sanctity of quillwork

Most tribes consider quillwork to be sacred, a gift from beings in the spirit world, charged with mystical power and blessings. It is therefore treated with great respect.

Craft societies

Among some, especially Algonquin tribes, such as the Cheyenne, there were special societies or guilds for women who were allowed to do quillwork. Cheyenne women who were not members of this sacred embroidery society were not allowed to work with quills at all.

The society had a set hierarchy, graded according to skill and the amount of work done. At the highest level were the older women with the most experience. These women were responsible for the quality of the work and the compactness of the patterns.

Patterns were obtained from higher powers and were sacred in nature. Women at the lowest level were only allowed to decorate certain simpler items, such as moccasins. At higher levels, it was possible to decorate, for example, baby carriers. The most skilled women were allowed to decorate such large-scale projects as buffalo robes.