Brain tanning is an ancient, traditional and natural method of processing hides and pelts. It was known not only to the Native American peoples of North and South America, but was once used by the ancestors of all modern people around the world, including our ancestors. For example, the clothes of the famous glacier man Ötzi, who died some 5,300 years ago in the Alps on the present-day Austrian-Italian border, were made from hides and furs tanned by animal brains.

In essence, it is a primitive variant of fats and oils tanning. The brain contains a large amount of fat that lubricates the hide fibres, making the leather soft and supple. Theoretically, any other fat can be used, but it has been experimentally found that nothing compares to the quality of the brain-tanned hide.

All of the hides and furs used by the native people of the Americas throughout history until the early 20th century were tanned by rubbing animal brains into the skin. After that, this method was forgotten because the Indians began to use only cloth instead of the tanned hides.

Although brain tanning is hard and strenuous physical work, it was performed exclusively by women, with men not taking part in the process at all. The men’s work ended with the killing of the animal or its transport to the village.

Hides and furs, hand-scraped and tanned by the brains, are of much higher quality than those tanned industrially with chemicals. They are usually much lighter, more airy and more durable than their industrial counterparts. They are also more permeable to vapour, with much better “breathing”, making them more suitable for making clothes. Their main disadvantage is that they are much more expensive than industrial leathers, due to the high proportion of arduous manual labour involved.

Brief description of Indian brain tanning process

Fleshing

The hide of a killed animal was skinned and fleshed, which means that all connective tissue, meat, fat and membranes were removed. Fleshing could be done in different ways, depending on the tools available and the size of the hide. Smaller skins were usualy fleshed on a smooth wooden beam. A sharpened rib from a larger mammal, such as a bison, or a steel flashing knife was most often used as a tool.

Larger hides, such as those of bison, elk, or moose were laced into a wooden frame or the edges of the hide were pegged to the ground with wooden stakes. The tissue then was removed with a serrated-bladed scraper made from deer bone or later, steel. Such a tool was very effective in tearing and removing the subcutaneous tissues, of which buffalo skin, for example, has a large amount.

Bucking

Some hides could then be bucked by immersing into a solution of water and ash for several days. The ash with water create a strong lye that opens the hide fibers and facilitates easier penetration of the brain solution. Properly bucked hides should always be left in running water, ideally in a stream or a creek, for at least a day to wash out any alkali and to get the pH to neutral.

Hair removal and preparation for braining

If a hide was intended to make into a hairless leather, the hair, and the upper parts of the hide called the epidermis had to be be removed. This can be done in two different ways — wet scraping or dry scraping. Pre-reservation Plains Indians certainly used both methods. Neither method is better or worse, and each has advantages and disadvantages; the better choice always depends on the specific situation, especially the type and size of the hide being tanned.

Wet scraping is more suitable for processing smaller and thinner skins such as deer, antelope or bighorn sheep, while dry scraping is better for larger hides as a moose, elk or bison.

Dry scraping

Dry scraping requires the hide to be dried first. This can be achieved by lacing it into a frame or by pegging it to the ground with wooden pegs and then let it dry. When the leather dries, it hardens considerably. The hair and upper layers of the hide can then be removed with a sharp scraper with a steel or flint blade.

The great advantage of dry scraping is that the skin can be thinned considerably. This will greatly reduce its weight, the mass of the material, and thus make it easier for the brain matter to penetrate. This is particularly useful for larger and thicker hides such as bison. Without a significant thinning of a bison hide, it would be very hard to transform it into a robe, for example.

Wet scraping

The hair side of a wet or freshly skinned hide was scraped on a wooden beam with the same instrument used in fleshing process, that is an sharpened buffalo rib or a steel flashing knife. To scrape the skin in this way is rather exhausting work and requires intense physical strength.

Unlike dry scraping, thinning the skin in its cross-section using this method is impossible.

The difference between wet-scraped and dry-scraped hides is usualy easy to see. The surface of wet-scraped hides is rather smooth, whereas dry-scraped hides resemble suede. Dry-scraped hides also sometimes show scraper marks.

Plains Indians hide scrapers

There were primarily three different types of tools that Plains Indians used to process hides before brain tanning.

A flashing knife in European usage is simply a draw knife with a dull blade that may be slightly curved. Its handle is usually wooden and flush with the blade. In Indian usage, it was traditionally a sharpened buffalo rib with the ends wrapped in a piece of cloth or buckskin for easier grip.

A scraper is a type of Plains Indians tool made of a wooden or elk antler handle with a carbon steel or flint blade, attached to the handle by a rawhide thong. The blade sat at a 90-degree angle to the handle. This tool was used exclusively for dry scraping. It could be used to comfortably remove hair and the upper layer of skin called epidermis, or even dried subcutaneous tussie on the flesh side. The scraper must be razor sharp to work properly and easily remove shavings from the hide.

A flesher is a scraper designed to remove subcutaneous tissue from large hides that have been laced into frames or pegged to the ground. It was made usualy from a single piece of bone, or from a wooden handle and a metal blade. The blade was blunt and slightly rounded. The blade included teeth to help tear away the tissue.

Braining

The next stage of preparing hides, skins and pelts is the braining process. The animal brain is largely made up of fat, which acts as a lubricant for the fibres of the hide. Basically, any oil or fat can be used, even egg yolks, but nothing compares to the quality of brain-tanned hides. Brains can be used either raw or cooked. Brains can be get into the skin in several ways. The oldest and simplest way is to rub the brains into the skin by hands. In “hair off” leather it was is rubbed in from both sides; in “hair on” leather, only from the flesh side.

An alternative for “hair off” leather is to immerse the skin in a solution of water and animal brains. In some cases, a mixture of brain and liver may also be used, with the liver acting as an emulsifier. This means that it helps the brain to penetrate the skin better.

Saturating the skin with brains is quite a job, as each hide naturally resists absorbing “foreign” particles, which the brain certainly is. Therefore, the braining process must be repeated until the skin is completely saturated.. With wet-scraped skins, brain penetration is a real chore, and the braining procedure must be repeated many times and very intensively. In dry-scraped hides, the brain penetration is a bit less troublesome, as the suede surface accepts the brain more easily.

Drying and softening

The next stage is softening. This is a quite physically demanding and strenuous step. The hide is first allowed to dry for a while and while it is still damp, it is pulled over a rope or a sharp wooden edge. This stretches the hide fibres during the drying process and prevents them from sticking together and thus stiffening the hide. The stretching should be repeated until the hide or pelt is completely dry, soft and pliable.

Smoking

The final procedure is smoking the hide. This stage is absolutely critical. If the tanned leather is not smoked, it will stiffen after soaking and drying. During the smoking process, formaldehyde enters the skin and strengthens the bonds formed by the brain oils between the skin fibres. When the leather is saturated with smoke it will not be impervious to water, as is sometimes incorrectly claimed, but will behave differently in contact with water than unsmoked leather.

Leather that has been smoked will not harden to a rawhide stage after getting wet, but will still be soft, or will soften when rubbed between the fingers.

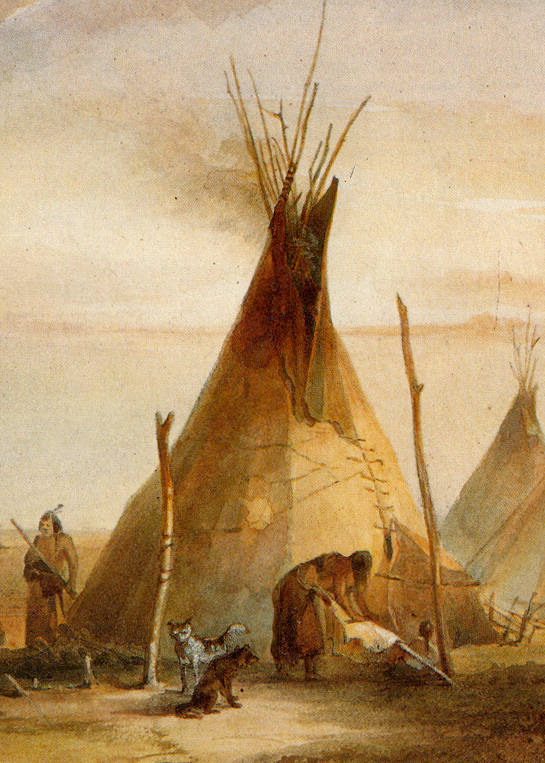

The Plains Indians used special conical or other structures made of wooden branches or logs to smoke the hides. Larger structures (like tipi frames) were used for larger hides, such as buffalo, and smaller structures were used for smaller hides. In the middle of the structure was a firepit. A fire was built in the center, below ground level and then covered with punk to create as much smoke as possible. The hides were then placed on the wooden frame to expose them to the smoke. They needed to be moved around the wooden structure so that all parts were exposed to the smoke evenly.

Pelts were only smoked on the flesh side, while buckskins and other hides without hair were smoked on both sides.

In some cases the smoked hides were washed in water to remove most of the smoky odour and and provide a uniform colour.

The many faces of brain-tanned leather

Brain tanning is a craft as well as a science and even just mastering the technology is not nearly enough. The final product — the size, thickness and quality of the leather — depends on a number of parameters. In short, each hide is different. Leather from a bison is different from than that from a deer, which is different from, for example, an antelope or a bighorn sheep. Hides from animals hunted in winter are different from those hunted in summer. The skins of female animals are different from those of males, and the age of the animals also matters significantly.

The same hide can be tanned to different degrees of softness or hardness. For example, insufficient scraping or dressing can result in a tougher product, which can sometimes be desirable.

Plains Indians made a variety of products from hides and pelts, and each type of product required a different quality, size, or stiffness of hide. The makers chose just the right leather for each project. For example, only the hides of young buffalo cows, usually no more than three years old, which had been hunted in the summer, were used to make teepees on the Plains. Buffalo, elk or moose hides were used to make robes, and the hides of females were often used because they were much easier to tan and were more uniformly thick than skins from males.

On the northern plains, the Indians most favored bighorn sheep hides to to make dresses, but deerskins were also used. Elk hides, which tend to be rather thicker, could also be used for more casual clothing or made into robes.

Myths

It is often said that every animal has enough brains to tan its own hide. This wisdom is said to have come from the Indians. Unfortunately, practice shows that this is not very realistic. For example, the brain of a buffalo, in terms of volume, might actually be enough to tan the hide from a much smaller deer, but certainly not a buffalo hide forty square feet in size. In my estimation, tanning takes significantly more brain matter than the animal actually has.

It is also sometimes suggested that American Indian women chewed the skins. Chewing the skins actually has nothing to do with the processing of them; the skins were processed exclusively with the tools mentioned above. The notion of the chewing of skins by Indian women is probably entirely fanciful.